Nicotine misconceptions: Sudhanshu Patwardhan on causes, consequences, and potential cures

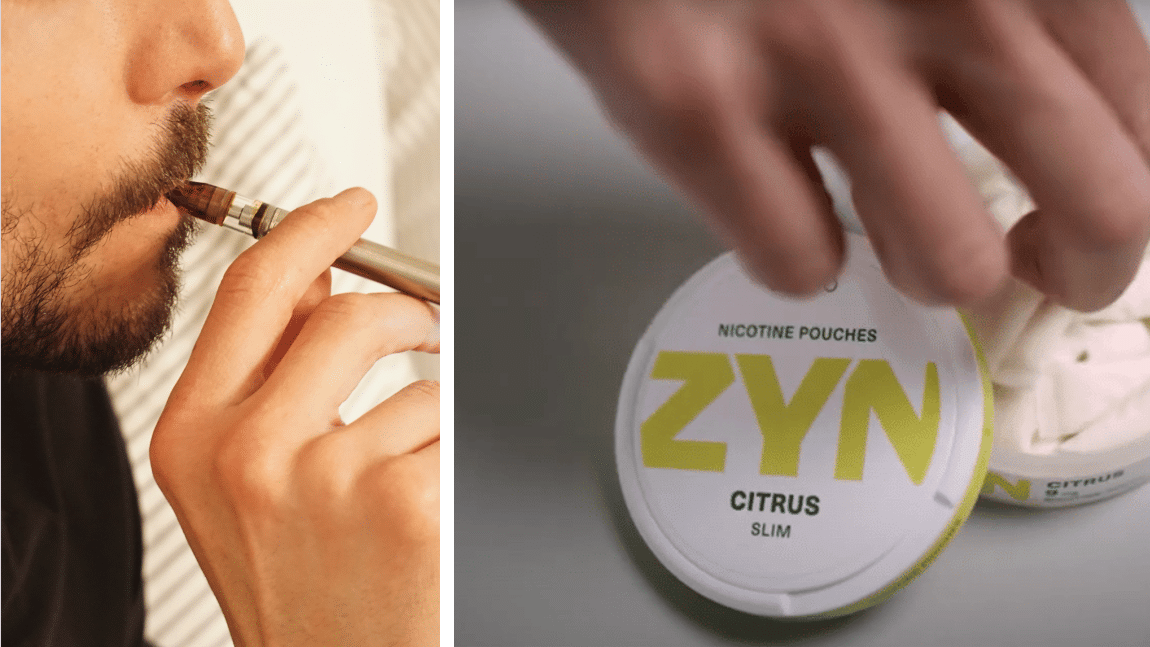

Snusforumet catches up with Dr. Sudhanshu Patwardhan to learn more about the harm reduction expert’s recent paper on nicotine pouches and why nicotine misconceptions are so widespread.

Patwardhan – also known as Dr. Sud – is a British-Indian medical doctor based in the UK. He co-founded the Centre for Health Research and Education (CHRE), which brings together medical and public health experts to work on cancer prevention projects in the UK and South Asia.

Together with Swedish nicotine researcher Dr. Karl Olof Fagerström, Patwardhan recently published a comprehensive review on nicotine pouches in the hope of providing guidance to policymakers and public health experts exploring different forms of regulation.

Patwardhan agreed to answer some questions from Snusforumet about the paper and how to tackle the persistent nicotine misconceptions that often hamper harm reduction efforts.

Why have you chosen to take a closer look at nicotine pouches?

The global disease and death burden from risky forms of oral tobacco such as gutkha, zarda, naswar, and American chew products – as well as from smoked tobacco such as cigarettes, bidis, cigars, cigarillos, and shisha – is huge. There are over a billion current users of such tobacco products, and over 7 million annual deaths from their long-term use.

One of the most common nicotine misconceptions is that nicotine, in quantities consumed in cigarettes or pouches, is carcinogenic.

Sudhanshu Patwardhan

The success rate of quitting such risky forms of tobacco is unacceptably low and the rate of relapse among quitters is too high. Thus, it’s crucial to innovate and develop better cessation products and services. And we believe nicotine pouches could be one such cessation option.

What are the main conclusions of your paper?

Nicotine pouches – due to their composition, expected consumption patterns, and based on some preliminary research – seem to have great potential for helping current users quit their consumption of risky forms of tobacco.

However, we also conclude that to realise the category’s public health potential, a wide range of stakeholders have to do much more research and engagement with the scientific facts regarding these products. This includes the industry, public health experts, regulators, and consumers.

What are some of the most common nicotine misconceptions?

One of the most common nicotine misconceptions is that nicotine, in quantities consumed in cigarettes or pouches, is carcinogenic. This persistent myth that nicotine causes cancer, combined with broader nicotine illiteracy, is at the root of the hesitancy among many healthcare practitioners to prescribe adequate nicotine replacement treatment for managing the cravings and withdrawal symptoms among their smoker patients during their quit attempts.

What are the main causes of nicotine illiteracy and why is it so widespread?

Risks from tobacco use became widely understood in the middle of the twentieth century. It is likely that the communication of the risks and harms from the then prevalent forms of tobacco was done in simple narratives that bundled cigarettes, tobacco, and nicotine into one interchangeable identity.

No education curriculum or public health campaign has bothered to de-construct the simplistic “smoking=tobacco=nicotine=harm” narrative.

No education curriculum or public health campaign has bothered to de-construct the simplistic “smoking=tobacco=nicotine=harm” narrative.

Sudhanshu Patwardhan

Medical curricula in countries such as India focused on the harms from tobacco smoke, the harmful effects of local forms of oral tobacco products on the oral cavity, and the fact that nicotine was the addictive substance in these products. However, not much effort was spent previously or is spent today on helping medical graduates understand how and why nicotine replacement therapy products are on the WHO’s model essential medicines list, or on how doctors can help their patients quit risky forms of tobacco.

This requires a nuanced understanding of what in any given tobacco product causes harm, what makes it addictive, how the two can be separated, and how nicotine replacement can help the users manage their craving and withdrawals when quitting risky forms of tobacco.

How do you view nicotine pouches’ potential as a harm reduction tool?

If manufactured to high standards, without adding toxic chemicals, using pharma grade nicotine, and keeping nicotine levels comparable or lesser to that from cigarettes, pouches can be an affordable and appealing alternative nicotine delivery device for current users of risky forms of tobacco. That by definition, would meet our criteria for a potential harm reduction-based cessation tool.

What is your message to policymakers currently looking at how nicotine pouches should be regulated?

The need for adequate nicotine replacement and for as long as necessary to prevent relapse is already understood at the policy level – the UK medicines agency has a harm reduction indication for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and the WHO has NRT on their model essential medicines list. This needs to be put into practice by healthcare professionals as well as consumers of risky forms of tobacco.

Our article specifically lists out the entire regulatory science-based research agenda for nicotine pouches. For example, nicotine pouches need to be regulated for safety, quality, nicotine strength, efficacy in cessation, and to prevent abuse and uptake among youth. In doing so, regulators should be driven by a clear need to maximise the category’s public health potential whilst minimising the unintended consequences.

What does the industry need to do to protect against nicotine pouches being lumped together with cigarettes?

The industry needs to learn from the past ten-plus years of global reaction and resistance to e-cigarettes. The industry needs to do their duty of care on the products and share this openly and transparently with the rest of the world. It would also help if the industry engaged relevant stakeholders before rushing to launch in markets that are still far behind in understanding tobacco harm reduction.