Swedish politicians resist anti-nicotine dogma, embrace pragmatic progress

As the EU wrestles with another round of tobacco policy reform amid a flurry of anti-nicotine propaganda, the debate about nicotine regulation shows no signs of letting up. In Sweden, however, where smoking rates are the lowest in Europe, political leaders are increasingly leaning into science — not stigma — when it comes to policy.

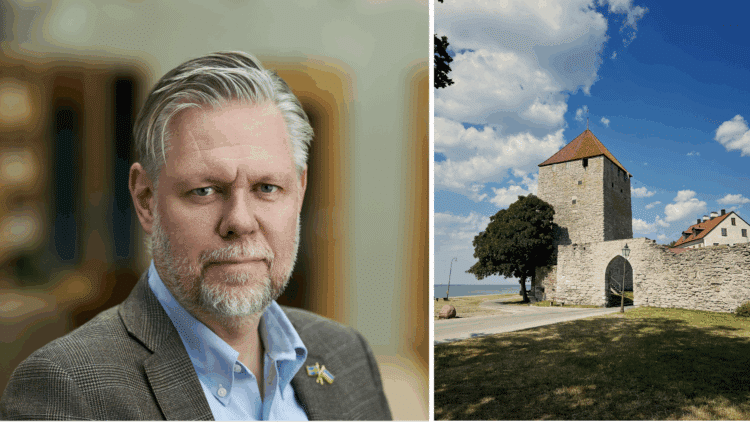

Rather than simply bowing to activist rhetoric, Swedish policymakers are instead asking hard questions and examining outcomes, according to Patrik Strömer, Secretary General of the Association of Swedish Snus Manufacturers.

“Politicians here are surprisingly well-informed — even more so than the general public,” he explains.

“Few of them are dogmatic. They’re asking what works in practice.”

Strömer’s observations stem in part from his observations at Almedalen, a major political get-together held every year in June on the Baltic island of Gotland. The nearly week-long event is full of seminars and panel discussions on a wide range of pressing policy issues, including how to best regulate nicotine and tobacco products.

A tradition of nicotine innovation

Sweden has a long tradition of nicotine innovation – from snus, to nicotine gum to tobacco-free nicotine pouches. Thus, it’s no accident that today Sweden boasts record-low smoking rates, with roughly 5 percent of adults smoking daily — the lowest figure in the EU. This achievement is largely attributed to the widespread availability and acceptance of snus and nicotine pouches as less-harmful alternatives.

Strömer believes that the role of nicotine innovation in Sweden’s success in cutting smoking is gaining traction. He sees a growing awareness among Swedish policymakers about the harm-reduction potential of products like snus and nicotine pouches despite continued anti-nicotine rhetoric.

“We have something close to a vaccine against lung cancer,” he notes.

“If all the world’s smokers switched to snus or nicotine pouches, the debate would be very different.”

Public health and policy: Aligned, for once?

Strömer emphasizes that political consensus in Sweden now largely supports both strong regulation to prevent youth access and continued availability of lower-risk alternatives for adults. One area that drew particular focus during Almedalen was underage access to nicotine.

“There is broad agreement that we need to fix this. It’s not about if we should act — it’s about how we do it,” he explains.

“No one wants minors getting access to nicotine, legally or otherwise.”

This pragmatic balance — restricting access for youth while protecting adult alternatives — stands in contrast to the often ideologically driven, anti-nicotine policies seen in other parts of Europe.

Frustration over anti-nicotine dogma

Despite this progress, Strömer sees areas where the debate remains stalled. He points to persistent activism denying the link between Sweden’s low smoking rate and snus use.

“It’s endlessly tiring to hear people say Sweden’s low smoking rate has nothing to do with snus,” he says.

“Of course it does. Snus leads to less smoking, not more.”

This refusal of anti-nicotine campaigners to acknowledge harm reduction is, in his view, a disservice to public health.

“It’s the same logic as ignoring seat belts because cars aren’t risk-free,” he says.

“Snus isn’t risk-free, but it’s much safer than smoking.”

Lessons for Europe: Don’t ignore the results

As the EU prepares for potential reforms of its Tobacco Products Directive (TPD), Sweden’s experience could be a model for a smarter, more health-focused approach. Yet, says Strömer, ideological resistance remains strong in Brussels.

“There’s a strange unwillingness in parts of Europe to accept that people need alternatives,” he says.

“Too often, the debate gets hijacked by moral panic or outdated views on nicotine.”

Still, Sweden’s position is stronger than ever. With daily smoking rates at historic lows and WHO’s “smoke-free nation” threshold already achieved, the country’s public health outcomes speak for themselves.

“It’s time to stop being embarrassed about our success,” Strömer concludes.

“We’ve done something right — and it’s something others could learn from.”