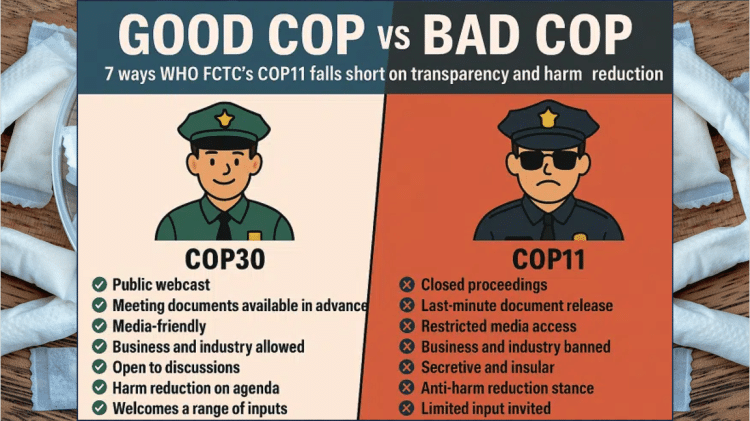

COP11 vs COP30: 7 ways FCTC falls short on transparency and harm reduction

As the WHO’s FCTC COP11 prepares to gather in Geneva, the UN-backed COP30 is also set to kick off in Belém: two COPs, two countries – and two wildly different approaches to tackling global challenges. Snusforumet unpacks how COP11 stacks up against COP30 on transparency, media access, and willingness to embrace constructive solutions. Spoiler alert: not all COPs are created equal.

Two big COPs, two very different vibes. Starting November 10th, COP30 will throw its doors open to governments, youth, cities, scientists, and – brace yourself – business. Starting a week later, COP11 prefers velvet ropes, last-minute paperwork, and a reflex to treat all nicotine the same as smoke.

If you care about policies that actually reduce harm and the difference is night and day. Here’s a look at some of the biggest differences between the two UN-backed COPs taking place this November.

1) Lights on vs. lights dimmed

COP30 publishes schedules, session pages, daily observer updates, and maintains open press channels and webcast archives so the world can watch and scrutinize in real time.

COP11, on the other hand, states that meetings are “public unless decided…open or restricted,” but only some sessions will be livestreamed; accredited media may attend open sessions (which often end up being the minority). That’s formality doing a lot of work.

2) Broad observers vs. selective gatekeeping

COP30 invites a wide ecosystem of observer constituencies and NGOs representing youth, researchers, cities, labour, as well as business and industry. There are even organised briefings to help these groups actually engage. Side events and exhibits are explicitly designed for observers to exchange ideas and showcase solutions.

COP11, meanwhile, filters observers through Article 5.3 (no perceived “industry influence”), with a track record of rejecting consumer groups and others. The signal is clear: fewer outside voices, especially those who talk about harm reduction.

3) Built-in media access vs. media on a short leash

COP30 runs a transparent media accreditation process, hosts press facilities, allows observers to book press conferences, and points journalists to a permanent webcast/archive. That’s how public accountability works.

COP11 requires accreditation too, but then adds the “open or restricted” caveat; it promises some livestreaming and a closing presser. It’s media access with asterisks.

4) Early, searchable documents vs. last-minute dumps

COP30 posts provisional agendas, session documents and an overview schedule well in advance. Observers can plan, analyze, and respond.

COP11 has historically cut things tight. It was notable enough that the EU formally asked to amend the rules so the secretariat must circulate official conference documents 120 days before the meeting (instead of the shorter current timeline). If you’re looking for an example of EU legalese that screams ‘please be more transparent’, here it is.

5) Open to solutions vs. allergic to harm reduction

COP30 structurally welcomes solution-makers, from innovators to city networks to companies. because reducing harm to the climate requires new tech, finance, and practices. That’s why business, research institutions, and municipalities are inside the tent.

But COP11 treats non-combustible products primarily as a threat, not a tool. Harm reduction isn’t on the menu; prohibition is. Sweden’s smoke-free results with snus and pouches should be Exhibit A that alternatives can save lives. Instead, the WHO is warning COP11 delegates to “stay vigilant” out of fear that success stories might “derail consensus” that all nicotine is evil.

6) Dialogue with many vs. dialogue with itself

COP30 literally trains observers on how to engage (capacity-building briefings, observers’ handbooks, advocacy guidance) and even publishes “how to engage without observer status.” It’s not perfect, but it’s procedurally set up to hear different viewpoints.

COP11 sets criteria so tight that consumer and harm-reduction advocates rarely make it past the bouncer. That narrows the conversation to prohibitionist defaults – precisely the opposite of what you’d do if you wanted to compare risks and reduce the deadliest ones fastest.

7) ‘End game’ framing vs. real-world risk hierarchy

COP30 culture acknowledges trade-offs: it courts people who deploy actual emissions-cutting tools, then debates how to scale them. Messy? Yes. But it’s solution-oriented by design.

COP11 arrives with “forward-looking measures” meant to intensify controls, and even warns that if you restrict “tobacco products only,” users might switch to less harmful alternatives (heaven forbid they stop inhaling smoke). That’s not harm reduction, that’s nicotine absolutism.

Bottom line: COP11 is the ‘bad COP’

If the goal is to reduce smoking-related death in the real world, COP11 is the bad COP: closed, defensive, and suspicious of lower-risk alternatives like snus and nicotine pouches that have helped Sweden reach EU-low smoking rates.

Maybe someday they can learn from COP30 – the good COP – when it comes to transparency, process, and a desire for actual progress. It may not be flawless, but COP30 is recognisably transparent and built to surface solutions, even if they come from people you disagree with.